Wikimedia Commons

In 1624 the island of Formosa 'the Beautiful', now Taiwan, was chosen by the Dutch United East India Company (VOC) as a stronghold to control overseas trade traffic with India, China and Japan. In almost forty years the company built two formidable forts and was routinely pacifying the various tribes and taxing a small number of Chinese settlers.

In 1662, a Chinese force, loyal to the evanescing Ming dynasty, fighting an already lost war against the invading Manchus, swept the Dutch away from the island that had become of value - maybe for strategic ends, maybe for future use as a retreat.

Albrecht Herport was a Swiss soldier of adventure, the son of prominent burghers of Bern, who as a nineteen year old left his home to enlist at the VOC. In spite of low pay and the notorious high mortality of seafarers to the East, he remained eight years in service of the VOC, two more years than his contract demanded. He happened to witness the fall of fort Zeelandia on Formosa and went on to Java and to Ceylon. Back in Switzerland he wrote a book on his adventures, as was the fashion. He too became a high-placed burgher of Bern.

On the fifth of October we spotted the high mountains of the Island of Formosa, from which sight the steersmen estimated that we were about fifty miles Also from the distance of the island of Lambay (now Liuqiu) from the shore (13 km) as mentioned hereunder, we may conclude that these sailors used the Italian or Roman mile of about 1800 m., not the German or Dutch nautical mile of 7,5 km. from Tayowan Tayowan was the name of a Chinese settlement in the 16th century. It became the main base of the Dutch colonists in the next century, flanked by fort Zeelandia. It is now part of the city of Tainan. The next day we saw the Island of LambayIn the source text it is called 'Laggimoi'. The editor, S.D. l'Honoré Naber, assures us in a note that Lambay is meant. , which lies about eight miles from Formosa in the sea.

Toward evening we saw mount Tancoya, and the Monkey Mountain, at a small distance of which a freshwater stream, called Bangsoi The Linbian river in what was then called the Pangsoya area, SW Taiwan., flows into the sea. We dropped anchor and had to stay one day and two nights at this place due to a contrary wind. The following day, early in the morning, we lifted our anchors again and in the afternoon we sailed into the southern roadstead of Tayowan, where we found one of our ships that had been forced by strong wind in this direction.

After our admiral had gone ashore, the Governor, called Frederick Coyett, sent out several sloops and boats to take us from the ships, first of all the sick, about six hundred men, who were all too weak to put one foot before the other and had to be carried to the infirmary. The ships were then brought into the Pescadores Port as a precaution against the sudden squalls that arise here. The Pescadores (so named for its excellent fishing) lie twelve miles from Tayowan and contain some broken islands, between which ships can anchor comfortably.

The island of Formosa lies twenty three degrees to the north of the Equator and so does Tayowan, which lies at a cannon's shot According to Wikipedia, 'Saker (cannon)', a common saker cannon had a range of about 2000 metres. distance from Formosa. The island (Tayowan) lies at a distance of 24 miles from the mainland of China and 12 miles from the Pescadores. It is about two hours long and a quarter of an hour wide. Lengthwise it extends to the east where at low tide Formosa can be reached on foot. This barren and infertile place is the site of the Dutch headquarters, called Zeelandia, comprising the residence of the governor. Next to other homes there are some warehouses containing the precious goods they trade. About a pistol-shot About 50 m. from this settlement lies an outpost with houses mostly built by Chinese, who bring all kinds of precious goods from China to barter with the Dutch.

Formosa stretches 200 miles from south to north and is about 50 miles wide from east to west. There are several high mountains, most of them still unexplored but by the inhabitants. The quite fertile plains around them are inhabited, apart from the natives, by thousands of Chinese, who have taken refuge there because of the long-lasting war they wage against the Tatars by whom they are violently and constantly oppressed. But they have to pay hefty tributes and taxes to the Dutch East India Company. These men are very industrious in cultivating and planting the land.

From time to time earthquakes are felt, often heavy ones, one of which occurred in my time. In January 1661, early in the morning, around six o' clock, the earth started to shake at its seams during about half an hour, in such manner that one's only thought was that the Earth was about to burst and fall apart. The quake made twenty-three houses in the outpost fall over and split the settlement of Zeelandia from one end to the other. The quake was followed by a slow movement, like that of a ship that is moved by the waves from one side to another. This lasted for three hours during which time no one was able to remain on his feet. In the harbour three ships at anchor were so mightily swung by the movement of the water that they were sure that they were about to capsize or else to burst. Here we observed an unspeakable wonder by God, as the movement made the water rise so high that it seemed much higher than the land. These movements, in the sea as well as on land, continued to be felt for six weeks. Afterward the earth was found on many places ripped open, especially in the mountains, and the natives said that they had never before experienced such a terrible earthquake. When asked what the quake was caused by, the Chinese answered that strong winds are hidden in the Earth and find no outlet, so they move the ground.

The whole year long there are heavy fall winds here, causing great danger for the ships that are at anchor. Consequently, as soon as the skippers perceive a cool wind, they cut the anchors, having no time to wind them, and take to the high sea, because there are many blind cliffs and sandbanks.

We saw the wonders that a strong wind may work. One ship that lay at four anchors in the northern roadstead was overturned by the wind. Moreover, a loaded galiot that lay at four anchors, lost its anchors and was lifted by the wind from the water over Baxamboy, a sandbank, and transported about a musket shot 200 - 300 metres away from there.

In the unknown mountains of this land lives a species of more or less totally wild people, who have a nub above their behinds like dumb beasts, usually a span According to Wikipedia, 'Span (unit)', a span is about 23 cm. in length. These people are very isolated among themselves. When they are able to capture other inhabitants, to whom they are very hostile, they take their lives in a most fiendish manner. In the mountains to the north of this land there is another species of unknown inhabitants, who, however, trade with other inhabitants in the following manner: they have a determined place where they go twice a year, bringing gold dust and other unrefined gold with them, which they leave on that place as they go away. Those with which they trade, in particular those of Faberlang, bring in the same manner other wares, such as clothes and other goods that wild men delight in. Then the mountain people come back to the place and when they think they get enough in return for their gold, they take the wares with them; if not, they take their gold back. Thereafter arrive the others and take what they find there, either the gold or their wares. They now know what to refer to the next time. The Dutch trade in the same manner with them. The place where they live is very unwholesome like all places where gold is found, especially for those that haven't been born there and don't know the means to arrive there without great danger and illnesses. Not far from there, on a small island, the Dutch possess a fortress, called Kelang, in which a strong garrison is stationed continuously. It has been built years ago by the Spaniards, who had a similar trade relation with the aforementioned mountain people, before it was conquered by the Dutch.

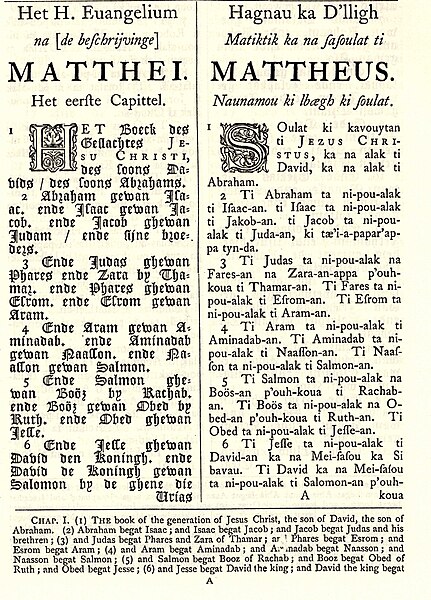

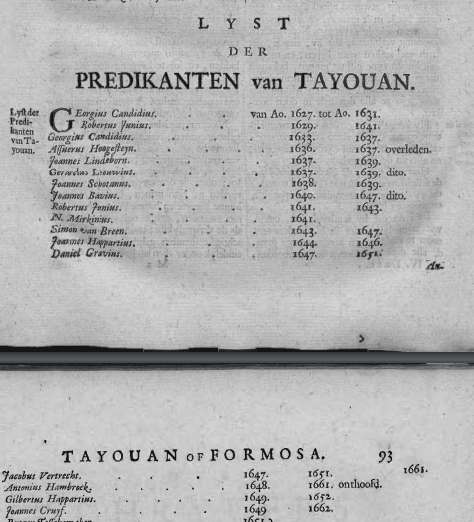

The inhabitants of the plains are all under Dutch jurisdiction and live in durable peace with them, because the Dutch establish various churches and schools in the area around the fort so as to be able to gradually bring them to the Christian faith. To this end the most learned Mr. Hambroek, servant of God's Word, has put their language Sirayan, spoken in the region around and south of Tayowan, and Favorlang, to the north, were described and used, also for translations, by various clergymen and eminently so by Georgius Candidius, Robertus Junius and Daniel Gravius. See William Campbell's Formosa under the Dutch (https://archive.org/details/cu31924023514403). in writing, using Latin letters that were totally unknown to them. Subsequently he translated the complete Holy Scripture in it. As a result many have been converted to our Reformed Christian belief within a short period of time, had their children baptised, able to read and write and educated in schools, because these are simple people of a good sort.

They who live in the south or in the southern regions are black of colour, those more to the north are somewhat whiter or yellow. They are good runners, able to keep up with, and even outrun a deer at full speed. They are also very nimble and skilful with bows, arrows and assagais, in the use of which they are instructed from an early age; every day they have a determined time in which they exercise target shooting and whoever doesn't hit the target receives no food until he does. This daily exercise goes on until they marry. Then they must dedicate their time to working, cultivating the land, sowing and planting, procuring food for themselves and their household. However they plant no more than deemed sufficient for their subsistence. Their houses and dwellings are quite badly and simply built. The clothes they wear they make themselves from the internal bark of certain trees that feels as soft as silk. They prepare and spin it to a beautiful quality for clothes and clothing. They wear long skirts like a shirt down to their feet. In the northern area however, when it is a bit cold, they take a fur or deer skin, which they prepare artistically and make it into a long skirt.

In the southern regions of this land, the mountain dwellers now and then descend to the plains with a big number of armed folks and cause great harm, especially in the Kardanang area, where they rob and steal everything they can lay their hands on, causing great damage to water wells too, ruining entire villages. When this happened to the governor in these days, he immediately convoked the inhabitants of several places with their armour and weapons, next to two hundred Dutchmen from the Tayowan garrison, with Mr Harthouwer appointed as their general.

On 14 February 1661 we embarked with a two hundred men strong force from Tayowan and, sailing southward, we were lucky enough to arrive within four days before Kardanang, where we were rowed ashore and stayed on the field for the whole of the night awaiting the rest of our men, who, being residents, came over land and joined us in big numbers that same night.

The land of Kardanang is ruled by a woman who provided us richly with food and drink. She is well disposed to the Dutch, who always call her by the name of the Good Woman of Kardanang. She is like a queen there.

In the night some scouts were sent out to explore whether the mountain roads were open and whether they were guarded. By sunrise they came back and reported that the roads were very narrow and everywhere hung with large rocks, bound with a piece of rotan or reed, which they cut when people come up the road; the stones roll over the narrow road, knocking down everything in their way. So it was agreed to walk around the mountain in order to pass through uncultivated land that was well-known to our folks that lived there. In the morning we set out and walked all day through the mountains until the evening, when we arrived at a stream where we prepared a place to sleep, keeping good watch in the night that followed. The day after, we continued our journey and in the evening we arrived under a mountain flank on the other side of which they resided. That night we kept a sharp watch, laying still without making any fire. Early in the morning we made our preparations and after each of us was provided with a bamboo filled with water, we started to climb the mountain, which would have been impossible because of its steepness, had there not been the wild growth to hold on. We also brought two field cannons that were carried up by natives, which they did easier than we could have done it without any load, as they are used to climbing the mountains. By noon we were halfway the mountain. Some of us had, because of the great heat in the sun, drunk all the water they had and were now half dead by the lack of it and unable to walk on, so our general saw himself compelled to send some natives back to fetch fresh water. In the meanwhile we continued forward and in the evening, one hour past sunset, the first banner reached the mountain top, but it took till midnight before the last man came up, as we were only able to proceed one after another. This climb caused us an unspeakable thirst, but we didn't find any water to quench it and during the night we kept such good watch that nobody was allowed to sleep.

Early in the morning after our army chaplain had said a public prayer with us, we started on our way again and continued for an hour and a half before we got sight of their dwellings. At this point we were divided in four companies and ordered to attack from four directions. So we charged from the mountain the people that awaited us in their houses (which were remarkably fortified; also the village itself was surrounded by a wall of black slate). As we approached, they started to fiercely shoot their arrows. So we shot at them from all four banners, beating the drum and blowing the trumpet. This frightened them greatly, in particular the cannon, as most of them had never heard or seen a cannon and many of them were felled. It made them wail so horribly that we understood they had lost courage. They instantly left their dwellings, jumped over the walls and run like cats downhill, even wounding some of us in passing, among others a seaman who had been left behind because of his great thirst and carried a load of several hundred measures of gun powder for the musketeers. They killed this seaman and tore him into pieces. Each of them grabbed the piece of flesh or bone that he could obtain. Then they dispersed the gunpowder over the ground, thinking that it would grow. They run into the bearers of the field piece, who, being quite defenceless, dropped the gun and made away. Coming upon this piece of artillery, which was placed on a wheel carriage and loaded, not knowing what to do with it, they wanted to burn it. So they lit the carriage, which, being tarred, easily took fire and a great number of them remained standing around it. But as soon as the flame reached the pan or the touch hole and the cannon fired, they all fell to earth and let it lie where it was without touching it any more. A squad of our men went to retrieve it.

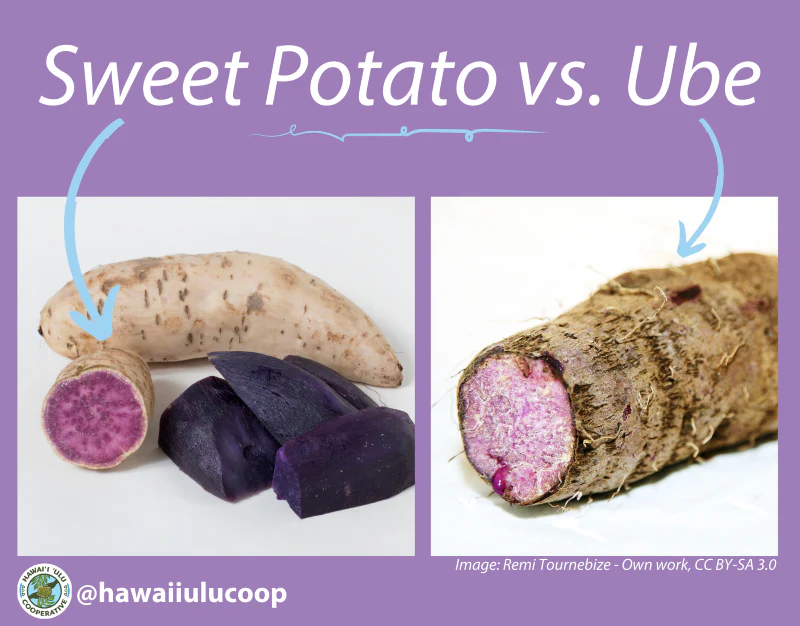

In their houses we found a drink they call Massikau, which is a good beverage, made of rice and buried some years under the ground. We also found dried ube, purple yam a plant root that is eaten instead of bread, as well as the meat of pigs and deer, buried under the earth and mixed with the bark of certain trees with which they are able to conserve the meat so well that it seems to be naturally salted. We also found many death's-heads in their houses, which they conserve from their enemies in order to remember their own, or their ancestors', splendid deeds. And which, if they want to make merry, they use as goblets. We stayed three days in this place and then set fire on everything. Thereafter we went back, early in the morning, taking the shortest way, the one that was hung with stones. When we had descended part of the way from this mountain, we saw them returning to their houses and extinguishing the fire. By evening we were back again at Kardanang, where our Commander sent us to the tents and, as we had discharged our duties well, he ordered twenty pots with Massikau and some cans with Arak to be provided to us.

The next day, the twenty-seventh, all our men were conducted to the ships again. Our Commander, however, and some other officers rode on horseback to Tayowan. We lifted our anchors, sailed off and arrived on the third day on a heavy cannon's shot distance from the roadstead there. Here our ship, called Maria, became stuck on a sandbank, which we hit three times in a row. So we fired immediately a shot with our cannon to have the other ships rescue us and save us from doom. But the ship turned, praise God, and came loose. That day we reached the roadstead and were brought ashore by boats and dinghies. We marched in full armour past the home of the Governor, around which, in order to honour him and as a sign of the victory that we had achieved, we fired a gun-salute.

On the fourth of March an envoy was sent from Tayowan to the Chinese coast; he departed with three ships from Port Pescadores. Also the other ships were provisioned and two of them, loaded with sugar and deer pelts, were sent to Japan and two that had already been loaded with pepper, to Persia. The remaining three sailed with Mr. Van der Laan, who had been our Admiral and had brought us with him from Batavia, back to that place with some high and lower commanders, as the Governor of Tayowan did not consent him to sail to Macao with his fleet and troops and those that he had brought from Batavia, to besiege the fort of the Portuguese. This was because the Governor himself was awaiting the enemy any day.

On the twenty-ninth of that month twelve men were sent from Tayowan to Pinaba, a place on the other, eastern side of the island of Formosa, to reinforce the garrison there. A few men were sent to Farbaron and Ilap, two quite unwholesome places, where nobody remains in good health for more than nine days. Some were sent to Tancoya and the Freshwater River, two landing places from where to occupy the land. Furthermore about fifty soldiers were shipped to Tamsui and Kelang (which places lie approximately sixty miles north from Tayowan) to reinforce two forts and other landing places and sea ports of this land, in particular fort Siccam, which is also situated on Formosa's mainland, opposite Zeelandia.

On 6 April some Chinese were caught on land who, dressed in Dutch clothes, had stolen from other Chinese who lived there, on Formosa. They were led captive to Tayowan and hanged shortly after.

On 15 April at about twelve o' clock at night, a strange noise arose from fort Zeelandia, on the bastion called Middelburg. At this hour, as all men slept in the guard house, we all jumped up from our sleep and each of us took hold of his gun. Some lit their wicks, some took their sword in hand, others put on their cuirass, others again grabbed their spears, so they were all milling around. If one asked the other what was going on, the other responded with the same question, nobody knowing the answer, till, finally, and with great effort, we regained silence. This was a first sign of the heavy siege that was to follow and of our great misery. In the roadstead were three of our ships that on the following day, one hour before sunrise, were seen by us as if in a light flame and that shot their guns without us hearing a blast or any noise. Conversely, those that were on the ships saw the fort as if on fire and as if also there artillery was fired. But when day broke we saw that nothing had happened. During a sequence of nights a multitude of ghosts was observed that fought each other on the field in front of the fort.

On 29 April before noon a man was seen in the water in front of the new building, who raised himself three times out of the water to show himself, without us being able to find someone who was drown. In the afternoon a mermaid was seen under the bastion called Hollandia, with long yellow hair, who raised herself three times out of the water. All these things were signs and portents of us becoming besieged.

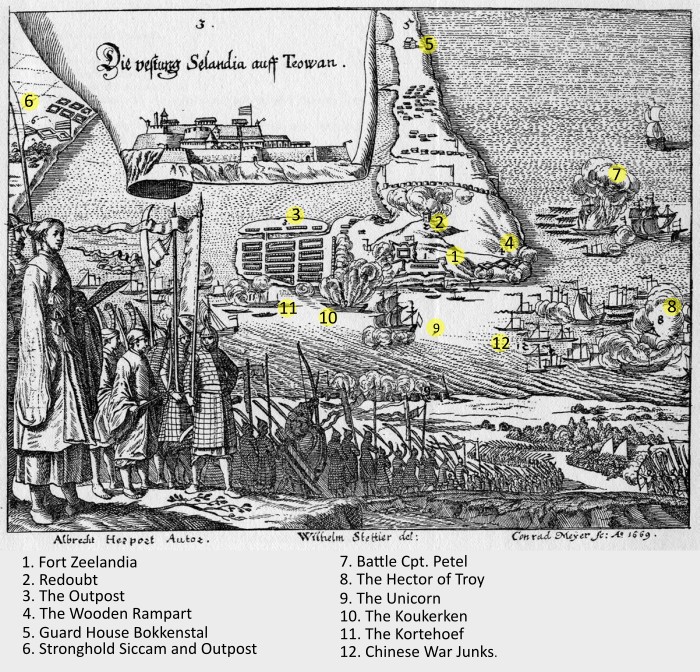

[A note of the editor of 'Reisebeschreibungen', S.D. l'Honoré Naber, on page 64, describes the theatre of the siege:

Zeelandia, stronghold and village, lay at the fat end of a very narrow strip of headland extending from the mother island to the north. To the west this headland was washed by the sea, toward the east by a bay (a kind of lagoon). Across from (to the east of) Zeelandia, on the other side of the Bay, lay the village Provintia (maybe identical with Sakam or Sikam). Here a small stronghold had been installed. A sand bank, partly consisting of a tidal flat, extended to the north-east of Zeelandia. This was the "Bar of Baxamboy", which contained two waterways: 1. the Southern Canal, 2. the Northern Canal and, still more to the north, a third, less used canal, the Gap of Laggimoy. Laggimoy was a very small fishers' village on the south side of this waterway. From Zeelandia the Southern Canal gave access to Southern Roadstead, the Northern Canal to the Northern Roadstead. On the bank of Baxamboy a redoubt had been built, called Zeeburch.

In Coyett's days there was another redoubt, the Utrecht, on the narrrow headland.]

In the morning and during the whole night of the thirtieth of April, there was a dense fog that made it impossible to see far ahead. But when the mist had disappeared we saw such a fleet of Chinese junks on the roadstead of Baxamboy that we were not able to oversee, let alone count them. There were so many masts that it looked like a barren forest. We watched them with apprehension and wonder, since no one, not even the Governor, had expected them. And we didn't know whether they were friend or enemy. They divided up in three fleets. The first one lifted its anchors, took sail and passed Fort Zeelandia for the south-side of Formosa, where it dropped anchor between Tancoya and the Freshwater River, about a four-hour distance from Tayowan. The second fleet sailed to the north-side of Formosa it seems the north-side of Tayowan, not Formosa, is meant here and anchored between Formosa's mainland and the sandbar Baxamboy (where an opening gives access to the inland port called Laggimoy's Gap) and put most of their men ashore. The third fleet remained in front of Baxamboy, at a safe distance—outside the range of a heavy cannon—from our three ships on the roadstead.

After they had put their men on land and occupied the roads, they attacked the inhabitants, Chinese as well as Formosans, and destroyed everything that came in their way. When our Governor understood what was happening, he immediately sent four hundred men to Siccam, to protect the stronghold. These troops, after crossing the strait and coming onshore, came suddenly upon the enemy, so they had to fight their way through with great loss and to withdraw to the fortress. But the others, who hadn't been put on land yet, were so violently pursued that they had no choice but to return to Tayowan.

Thereupon the enemy put up camp in front of the Siccam fortress, instantly cutting the besieged off from water. Day and night we heard charges from both sides. But the besieged, surprised by the enemy, suffered lack of provisions, especially of water, so after a few days they were forced to surrender the Siccam stronghold.

The Chinese who lived on Tayowan and Formosa in the area hold by the Dutch, most of them merchants or craftsmen, went to places they thought to be safe, taking as many goods with them as they could. As soon as the governor got word of it, he ordered them through a corporal and two soldiers, me one of them, to join us in resisting the enemies. We found twenty of them who were preparing to leave. When we told them to desist, they became hostile, and gave us a terrible beating with peddles and sticks they fetched from their ships. They robbed the corporal of his sword and inflicted several gashes to his head. There was no way out for us but to jump into the sea, where we stayed for about three hours until night came and they couldn't see us any more; we then returned to the fortress. Now we realised that also our subjects and fellow inhabitants had turned out adversaries.

During the night our captain, Thomas Petel, ordered us to build three batteries under the walls that were to shoot over the water; each one was provided with four cannons.

Early in the morning of the first of May, some slaves arrived who brought with them the son of captain Petel. He had been severely wounded by the enemies and his instructor, who was at his side, was cut into pieces. Infuriated, the captain commanded to beat the drums right away. He took two companies of the best troops, each of hundred men, well provided with ammunition and all necessary protection wear, and asked the governor's assent to meet the enemy in order to crush them in a battle. It was permitted. We boarded Chinese sampans - small vessels - as well as a galiot, and went to Baxamboy, where three more ships were lying on the roadstead, which were ordered to attack the enemies' junks on the sea, whereas we were to contemporarily assault the Chinese on the shore. We walked slowly along the beach until we saw in the distance our enemy approaching with a great force. This place is covered with many short pines, about the size of half a man, behind which some enemies had hidden whom we passed by unknowingly. As soon as our three ships reached the junks, our men rapidly shot their guns in such good order that they were able to follow each other up. The enemies, who had a great number of ships and guns available, answered with furious gunfire and incendiary arrows, with which they hoped to set our sails in fire.

After half an hour of fighting, we saw a great flame rise and heard a violent blast. We thought one of their junks had exploded, but as soon as the smoke had dwindled, we saw that it was the biggest of our three ships, the Hector of Troy, carrying one hundred men, who were all blown up together with the vessel, leaving no survivors. The other two ships fell back to the roadstead. This encouraged the enemies, who came gradually closer to the coastline and eventually sailed emboldened and with full speed in our direction. Our captain reacted by positioning his two companies a bit wider apart to make our small group looking somewhat bigger. Meanwhile a heavy gunshot was fired from fort Zeelandia together with other signs for us to return. But the Captain, who put his honour before his life, didn't give it any heed, but kept on engaging the enemy. When we had come at the distance of a musket shot, the enemy lined up and advanced about fifty or more bases A base is a small, naval breech-loading swivel gun. or double-barrel arquebuses to the ranks that were awaiting us.

We had field pieces loaded with scrap and musket bullets on the galiot and the sampans that accompanied us continuously along the coast. They started to shoot them at the enemy, soon after followed by the bases. We moved somewhat closer and started to charge in formations. But the enemy came with great clatter and noise out of its ambush and attacked us on the front and at the back. Heedless of our shooting they assaulted and surrounded us with their side-swords, chasing us into the water. We had no way out but to swim to our ships. Of the first group who reached a boat, too many entered it, making it capsize and most of them drowned. The others saved themselves by swimming. Some of us kept fighting in the water alongside the captain until he was killed. Then we boarded the capsized boat after having it overturned again and escaped in great danger from the hands of the enemy. Out of the two hundred men that set out, not more than about eighty saved their lives, most of them swimming to fort Zeelandia. Some of them remained about nine hours in the sea.

The weapons the Chinese use are side-blades, i.e. big sabres fixed onto shafts used as halberds. They also use bows and arrows. A quarter of them carry a white banner with a long steel peak, which they use instead of a spear. Some of their banners are long and narrow, like the vane of a ship; these are their victory-banners. Others are like standard vanes. Others again are composed of many pieces and parts of silk in all kinds of colours, with silver and gold and many images, especially of their gods, mainly their

joosje

Enne Koops and the redaction of the website Historiek (27-11-2023) say:

The designation 'Joost' in the Dutch expression Joost may know ('Who knows?') probably refers to Javanese 'joos', a term designating a Chinese deity or its image. This term is a shortening of 'dejos', which is derived from the Portuguese (and Latin) word 'deus', which means 'god' or 'deity'.

When the Dutch colonizers on Java heard the word 'joos', they transformed it into the Dutch name 'Joost' or 'Joosje'. As the term 'joos'—apart from designing a Chinese deity—for a long period was also used for other 'heathen deities or idols' in the words of the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (a historic dictionary of the Dutch languange, as well as a website), the word 'joos' acquired the meaning of 'devil'.

and still others, of devils, dragons and snakes.

These Chinese are armoured from head to knees. On their heads they wear a helmet that covers the entire head and neck, leaving nothing uncovered but the eyes. On top of the helmet sits a sharp peak with which they may easily transfix a person.

They maintain good order among their troops. When the occasion permits, their captains mostly move on horseback, one before the company, two at each side and two at the back, who immediately start hewing with their swords as soon as someone cedes more than even one foot.

On the second of May our two ships that were not secure any more in their usual roadstead, were sent off, one to Kelang, where two others were at anchor, in order to inform them, as well as the governor, of our besieged state, so he would know what steps to take. The other ship departed for Batavia in order to inform the general of our state of affairs, so he would be able to assist us with troops and ships.

Now the batteries under the walls were taken down again and the guns brought to the fortress from which, they thought, the outpost could be sufficiently kept safe with the cannons.

On the fourth of May we heard a great noise and violent gunfire, tam-tams and drums. They blew their horns and trumpets and seemed overcome with joy, without us understanding what it was about. In the evening we learnt that the governor of Siccam had been forced by lack of water and provisions to surrender the stronghold and that he had been carried off in captivity together with his wife and children and four hundred men.

Dispersed over the land there were many Dutchmen, mainly in fortified settlements: many hunters, school teachers and workmen who had not fallen into the enemy's hands and had gathered together. Part of them, about fifty men, all well-provided with guns, marched the whole night along the Freshwater River. When at dawn they arrived at a guard house that was known as the Bokkenstal ('Goat Shed'), they came under attack of the enemy. They defended themselves, putting the Chinese under such intense fire, that within a short time they had killed at least twenty of them. Courageously carrying on, they reached our stronghold Tayowan.

On the sixth of May all citizens in the town were ordered to leave their houses with their wives and children and to come to the fort. It was agreed that the town would be set on fire.

On the seventh of May, Captain Aeldorp was sent out with his unit to put the houses, even if mostly built of stone bricks, on fire. Among these was a warehouse in which the Dutch had stored many thousands of deer hides and that was burned to the ground. The enemies, who had been hiding in big numbers in the town, now were forced to come out and defend themselves. Meanwhile our party received assistance and got new hope to expel the enemy, who however was reinforced as well and deployed several bases and chamber pieces that caused great havoc on our side. As evening fell we had to withdraw. During the night ever more enemy ships arrived, bringing another five thousand men into the town. We sprayed them with gun fire from the fortress, but they didn't care as they were mainly out on rich spoils. And as we were forced to leave the town, most of the houses remained intact, especially those of the Chinese that were full of precious goods, gold and silver and all kinds of silk, as well as rich provisions of food and drinks, which fell into enemy hands and we had to do without. They also found two thousand manufactured sugar boxes commonly used by the Dutch to transport their sugar. These they filled with sand and earth and used them as ramparts in all streets, securing them against artillery fire. Thereafter they shot each night a great mass of burning arrows in our bastion in the belief that they would ignite our houses; but they were harmless.

On the twelfth of May our ships from Kelang came before the stronghold of Tayowan and asked for orders from our Governor, where they could go to be safe from the enemy. Our Governor ordered them to transfer their most precious wares, like the sugar they had loaded, to the smallest of the three ships so as to be able to bring it into the harbour. This ship, loaded in said manner, was about to navigate into the harbour. But when the Chinese, our enemies, took notice, they immediately set out with some of their vessels, called Gojas, and twenty other boats that could be steered with oars and held many men, toward it. As we were not able to reach them with our guns from the fort, we made a small stronghold on the beach and placed two guns on it, with which we hoped to keep the enemy at bay. But we were not able to cause them a lot of harm. The two other ships fired their guns at the Chinese and sunk three of their vessels. However, they wouldn't budge and intensified their efforts. Those who were on foresaid ship, only eighteen in number, received order from the Governor to set fire on the ship and to get away in dinghies and boats.

As soon as they clambered down on one side of the ship, the enemies climbed up on the other side and hauled up water in order to extinguish the fire. A few hundred men entered there. But when the fire reached the gunpowder, the aft end of the ship blew up. The men who found themselves at the fore of the ship wanted to take the wares that were still undamaged with them. But the flames kept advancing and reached the sails and the maintop that contained a chest full of handgrenades and other explosives, which ignited and flew around their ears. So in the end they had to leave the ship with great loss of lives.

The ship, called the Unicorn, was completely burned out. The two other ships, named 's Graveland and Vink, were then pursued by their whole fleet, consisting of about thirty junks. Our ships had a favourable wind and fired energetically at them, one gun after another. This lasted for two whole hours; when our men were out of iron bullets, they used sandalwood and sampanwood, which is as hard as iron, sawing it into pieces with which to shoot. The junks came so close to our ships, that these were no longer able to open their gunports, but had to shoot through them.

In the end they had to let these two ships go, which headed toward Japan, as the enemy was too powerful for them. And although we are not allowed to enter Japan with warships or ships carrying armed soldiers, we were however able to excuse ourselves, driven away as we were from the roadstead of Tayowan and pursued by the enemies, the Chinese. Moreover we had sufficient proof of that with the arrows that remained fixed in the hull all around the ship. So we had been forced to find a secure port and consequently were permitted by the Emperor of Japan to stay there as long as we wished.

On the fourteenth of May, King Coxinga directed himself and his bodyguard to the guardhouse Bokkenstal, where he made his camp and had his tents of red scarlet erected. He stayed there for some time with his three mandarins or field commanders. On that day a Dutchman, who had been made prisoner by the Chinese and had escaped by a ruse, came to us and informed us that the enemy had dispersed with a mighty army all over the country with the intention to bring the inhabitants, including any Dutchman that would be found, under their power. Those who were not willing to submit voluntarily, were forced with great indignities and misery. Among them was a teacher of the Divine Word who was dear to the Formosans, many of whom he had converted to the Christian belief, and respected by them. There were also many other Dutchmen with him. He had urged the Formosans not to surrender. They themselves also wanted to stay with them and not abandon them. These were horribly tortured and some of them killed in a gruesome manner. The above-mentioned clergyman was fixed to the cross alive, while the other Christians were compelled to stand before him with bound hands to watch his sufferings. Not only did the man remain upright in his duties, even in his deepest misery, but he spoke comforting words to the bystanders and admonished them faithfully to remain constant in honouring God and keeping true to the religion they had adopted, even if they, like him, would be horribly abused. This minister stayed alive on the cross until the fifth day, when he joyfully died.

Shortly after also a school teacher was miserably killed after his wife had been abused before his eyes, as they did to several others and in particular to their superiors, whose heads they cut off and stuck on peaks, as an example for the others.

On the twenty-third of May, in the afternoon, some men of the enemy army arrived with a white vane. Among these was the clergyman, Mr. Hambroek, who had been taken prisoner by the enemy in the very beginning. The Chinese sent him as an envoy with a letter to our governor in Fort Tayowan. The content of the letter was that if he would surrender the bastion, king Coxinga promised safe quarter; if not, that the attack would start promptly and even the youngest child would not be spared. This request was completely rejected. A reply was written that they had only gunpowder and lead to give and that they were resigned to defend the place until the last drop of blood. So the rev. Hambroek had to leave again with this letter, as his wife and three of his children were prisoners of the enemy and he did not want to desert them. He also had two daughters in the fort, one of whom married, the other still unwed. They saw their old father go with great sadness.

During the exchange of letters, a truce had reigned, but as soon as the king had received the governor's short answer, he gathered most of his forces to assault the bastion with all their might that same night. They entered the town with their big army, with artillery and provisions, with about twenty wicker ramparts which they raised in front of the houses and filled with earth. They installed their guns behind them and started shooting three hours before dawn, hoping to create an opening before the day broke so as to launch the assault at the coming of the day. We noticed their activity by the brightness of the flames and, guessing their intentions, we didn't sit still but put our pieces to work, using thirty of them to shoot at their operations. The shooting lasted an entire four hours. They caused great damage to the parapets that were very thin. Many persons were wounded by the shattering of the stones. When daylight broke and we were able to see what they were doing, we fired so intensely at them that they had to pause for a while as they were not able to reach their guns, because of the dead bodies lying around them. Moreover some of their wicker ramparts were shot in pieces. When our men observed this state of affairs, some of them offered to make a sortie in order to spike their guns. The governor gave his consent hereto. To this end sixty men were lowered at the outside of the walls, who immediately run to the guns behind the wicker ramparts and attacked them, while others, who were carrying hammers and nails, closed up the cannon vents. Meanwhile the enemy shot a rain of arrows from the windows, but could not do us much harm, as we were able to shelter behind the wicker ramparts.

When we had used all our gun powder and no support was coming, we had to retire. We took all the banners sitting upon their wicker ramparts with us as well as any other weapons. As we withdrew they pursued us with a few bases loaded with shrapnel, with which they wounded many of us, killing two. At our return into the bastion we were received affectionately by Mr. Governor who expressed his regrets that he had not sent assistance. So he at once made a request of volunteers willing to make another sortie in order to turn around the guns, dragging those they could with them to the bastion. There were instantly two hundred men who volunteered, to whom one hundred slaves were added to draw the guns.

The enemies had in the meantime provided themselves with guns, which they had brought into the first houses and shot uninterruptedly at our rush forward, wounding some of us and taking down others. They met us with groups of lancers and men carrying side-swords. On both sides, we defended ourselves bravely against each other. They would have beaten us because of their superior forces against our small number, hadn't several cannon shots been fired from the fortress, mowing down our men as well as theirs. We were not able to do much with their guns, as we had our hands full with the enemy with which we skirmished a full three hours long.

When we had lost about twenty men and were not allowed to stay any longer on the governor's order, we put fire on all their wicker ramparts and dragged a piece of artillery with us. Some of us also took an armful of arrows and so we returned to the bastion. The arrows that we had picked up and brought with us, were to serve us as firewood, of which we had a great shortage. Towards evening another hundred of our men were sent out to obstruct their guns. After having carried out their assignment they returned with some losses. During the night the enemies wanted to use their pieces again, but one of them burst with the first shot; so they carried all the others away. That night they made four fortifications in all the four streets and placed their bigger guns upon them, which they continuously fired toward the fort.

The Mandarin, or commander, of the Chinese, who had been ordered to assault the bastion and so far had not been able to accomplish anything, was decapitated on the twenty-fifth of May, together with some of his officers, before the entire crowd of his soldiers.

On the twenty-ninth of that same month, the fire mortars appeared with which we started to shoot grenades and stones into their quarters. The first grenade shot came down in the broad street. The enemies hurried towards it, but did not know what it was and wanted to extinguish it with water. But when the wick layer Wick layer - the German text says 'Species', maybe from Dutch 'specie', mortar. had been burned, the grenade jumped amidst them and brought down and wounded many of them.

Early in the morning on the third of June, a Dutchman appeared in front of the fort. He had been our drummer in fort Siccam and had been taken prisoner there together with others and taken into their junks. He had entered the water during the preceding night and after seven hours of swimming he had reached us and was taken in. We received much news from him, among other things that the enemy some days ago had gone with two thousand men and about thirty Dutch prisoners to the land of the emperor of the South, (his realm comprises seventeen villages to the north as well as to the south on the island of Formosa and up till that moment he had shown himself a friend of the Dutch) without doubt in order to know whether the emperor would surrender to their violence or not. In the beginning the inhabitants, subjects of the emperor, showed themselves very friendly and gave them everything they wanted. The Chinese took their kindness for granted and felt so secure that they laid their weapons aside, as they didn't fear an enemy. The emperor then made a plan with his people to attack the Chinese by surprise during the night, which was brought to the knowledge of the Dutch prisoners so that they could regulate themselves accordingly. On a determined night they carried out their plan and killed more than fifteen hundred Chinese. The others, hoping to save themselves and hide, run into the sugar fields, which, when it was detected, the emperor ordered to set on fire on all sides in order to force them to show up. Most of them were killed and very few were able to escape. After this fight, the Dutch who had been prisoners of the Chinese crossed the land of the emperor toward Tamsui. At a distance of three miles from this place they were violently pursued by the natives. When they had to cross a river they were attacked in the water. Eight of them had their heads chopped off and most of the rest were wounded by arrows. Those that were able to escape reached our people at Tamsui that same day. We learned from the drummer that as a consequence of the long rains that had lasted six consecutive weeks long, many Chinese men had died.

In the night of the fifth of June we heard a big blast over the water, coming from the direction of Siccam. In the morning we learned that one of their war junks with a few thousand of pounds of gun powder had caught fire and exploded.

In the night of the thirteenth of that same month they made a big noise, shouting and using horns and other musical instruments. So we thought that they were planning an assault, the more so because the preceding day we had observed many assault ladders. They turned some of their junks into fire ships in order to set fire on our longboats and the vessels that were anchored under the walls of the bastion. They arrived with ten sampans (their small boats) together with some fire boats, with many men in them. As soon as we saw them we opened fire from the four bastions, sinking some of their sampans. They did not pay any attention to it, but tried to manoeuvre their fire ships so as to set fire on our vessels and when they succeeded in it, they withdrew. But our men put out the fire.

While all men in the fort were fighting and we were intent on an assault, someone's bandolier suddenly caught fire. He threw it away from him and caused the fire to extend. The guns were shot empty and the boxes containing cartridges and fifty hand grenades took fire as well, causing much damage when they exploded. On the sixteenth of June five horsemen rode out according to custom as a mobile guard. When they were not far from the enemy army, they noticed they were pursued by thirty Chinese horsemen with bows and arrows, carrying side-swords as well. When they wanted to turn back, their way was cut off by about one hundred footmen who had been hiding in the bushes. These five horsemen, when they noticed the enemies to the front and at the back, offered a brave fight. But one of their horses stumbled and was surrounded. The horseman however defended himself in a manly way, beating around with his carbine after having emptied it, until he died, having received many wounds. When this was notified to King Coxinga, he had the man buried as a hero and his entire army shot their guns to honour him, even if he had been an enemy.

On the twenty-fifth of the same month our constable wanted to fire a grenade. But when the filler layer had almost burnt, he didn't succeed in detonating the bomb and the grenade jumped out at a height of not more than a man's length. A piece of it, still burning, fell down on a casemate gun loaded with musket bullets, that fired and wounded many of our men in a terrible manner. At the end of the month, that same constable was terribly wounded by the enemy. He received 30 wounds all over his body by shrapnel from a a gun.

On the tenth of July we saw a junk approaching from the south that carried a Dutch flag. It was thrown on the beach of Baxamboy by a fierce gale. So the governor sent a longboat in its direction to see what people where on it. They were found to be Chinese merchants arriving from Batavia and carrying much money. As the junk was gravely damaged, some of their men went into our longboat with the money chests they could take with them, promising our men half of it by way of salvage money. Some left the ship swimming. But the others surrendered to the enemy in order not to leave the money behind. These men had been underway from Batavia for two months and said that a new governor had been elected for Tayowan and was about to come to them.

On the fifteenth of the same month ten of our volunteers and a sergeant were sent out to see if we could seize one of their sentries. When we came halfway their army at Bokkenstal, we met three of their soldiers, two of whom we threw a cord around their neck so as not to call out and betray us. The third one escaped. From the two that we took with us we obtained, through much torture, some information we didn't dare to confide in, as they preferred to die over betraying their own people.

Some days after, we saw a ship approaching from the open sea. The following night a dingy was sent in its direction to see what kind of ship it was and, in case it was the new governor, to inform him how things stood. The case was as expected and his name was Kling. When he had understood our situation, he sailed to Japan as he had few armoured men with him and was alone.

Our enemy started to install two batteries at Baxamboy so as to shoot directly at the ports of the bastion and to deprive us of the place where we buried our dead, as we had to do each day, because there were many sick among us, up to a number of four hundred, apart from the wounded. Their sickness was partly scurvy, partly oedema, because for a long time we had only taken very bad food and water, without refreshments. And we were rapidly losing courage as there was no hope of relief.

On the ninth of August we saw a fleet of twelve ships coming from the south, which we hoped would come to our assistance, and it was so. When they had reached the southern roadstead and had anchored there, they sent a longboat to the shore, informing us that they had come to assist us and were well provided with men and provisions and that their admiral was called

Cau

Well-informed VOCsite identifies him as Jacob Cau.

In the Biographical Dictionary of the Netherlands ('Biographisch Woordenboek der Nederlanden'), Part 3 (1858) by A.J. van der Aa, Cau's career is described as follows:

CAU (Jacob) o Cauw, born May 1626 in Middelburg (Zeeland), became councilor of the Court of Batavia in 1661 but was in the same year ordered to sail post haste with a fleet of ten ships and about 500 men to liberate fort Zeelandia on the island of Formosa that was besieged by the Chinese pirate Coxinga. On 12 August he finally arrived with his flotilla on the roadstead of Zeelandia, but an oncoming storm forced him to cut the anchors and he disappeared from view. In addition, flute ship Urk ran aground and fell into the hands of the enemy, who consequently were informed about the general state of the fleet. At last, however, the ships came sailing back and delivered troops and war provisions. Now circumstances started to change to the advantage of the beleaguered garrison. Up to October Coxinga hadn't gained any major advantage on the defenders, but lost 8000 of his best soldiers and many junks. The Manchu, who liked the idea of occupying the stronghold that Coxinga held in China, offered their assistance, provided the Dutch would send some ships to collect them and would destroy the rest of Coxinga's forces in China as well. Cau offered to bring them over with five ships, but the commander, who was probably a better scholar of jurisprudence than an admiral, only got as far as the Pescadores and sailed from there to Batavia, passing by Siam. The besieged were terribly disillusioned; the three ships that returned denounced the cowardice of the commander and the hope to divert Coxinga into China went up in smoke. Cau was punished for his cravenness with only a small fine and a suspension of six month from service.

Half an hour later a fall wind arrived from the south and forced them to cut their anchors and sail as swiftly as they could into the open sea, where they were driven so far away that none of their ships could be seen any more. We were gravely saddened to have seen such a mighty fleet before our eyes and being so suddenly bereft of it. What saddened us even more was that toward evening on that same day we heard our enemies shouting at us that one of these ships had already been thrown upon the beach and wrecked and that they had caught some of the crew seeking refuge and had received much information from them. After eleven days we saw the fleet approaching again. They had sought refuge amidst the Pescadores and brought cattle that they had found there in order to refresh our sick. When they had come ashore and brought their war supplies and provisions, all preparations were made to attack the enemy with force. Five ships, equipped with all the necessary means, were ordered to moor in the harbour at the backside of the town so as to shoot their guns along the streets. Some boats and longboats loaded with hand grenades and

fire-pots

Fewr-bootten in the source text. NL: 'vuur-potten'. A pot filled with fire or stench generating material to be thrown into the enemy's ship.

Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal, Historische woordenboeken Nederlands en Fries

were to attack the junks. On the determined day the ships moved to the described place, but found the streets everywhere blocked with wicker ramparts and guns and so they were not able to accomplish anything with their guns, but to the contrary came under heavy fire from the other side. So they wanted to go back. But two of them remained stuck; one of them, the Koukerken, was stuck directly in front of the battery and was fired at so intensely by the enemy that most of the crew were wounded and had no force left to handle the guns and manage the ship. Those who had any force left jumped into the water and swam to the fort. Shortly after, the ship's aft flew into the air as the gun powder took fire. The bow however remained above water and the survivors tried to save themselves there. But the fire kept extending until it reached the bowsprit and they called pitifully for help. So the enemy came up to them with a few sampans, took the wounded and threw them in the all-consuming fire. The other ship, the Kortehoef, was stuck at a greater distance from their batteries, near Baxamboy. The skipper of this ship and some sailors took the dingy, put a grappling hook in it and made as if they would apply it in order to refloat the ship by winding: but they did not come back. The others, who were able to swim, entered into the water so as to reach the shore. No more than six men and a lieutenant remained in the ship, which during the night suffered many collisions with fire ships, till they, tired and resigned, decided to extinguish one of the fire ships and to jump into it, leaving their ship and saving themselves. As for our boats and dingies that navigated amidst the junks of the enemy with the intention to put them on fire, these were surrounded by the enemies that took two dingies as well as a boat with all of the crew with them. The others did their best to harm the enemy with hand grenades and fire-pots, but the Chinese were able to catch them with an extraordinary swiftness into their sails and to toss them back into our vessels, leaving our men no choice than finally to withdraw with many losses. In this battle about three hundred men were killed on our side, apart from the wounded. Their dead bodies floating to the enemy were handled in a shameful manner, their male member cut off and put into their mouth and so, floating down the current, sent to us. Some had their heads cut off, others were handled in another inhuman manner.

Furthermore those that had been imprisoned by the Chinese, on 4 May 1661, as mentioned above, and became aware that we had attacked the enemy on Tayowan, in the town, and also their ships in the water, assembled in the hope that we would win (though imprisoned, they were free to go where they wanted), obtained by deception and violence weapons from the enemy and went so armed to Siccam (where they had been taken prisoner, as we told above), hoping that we at Tayowan would have won. But they were deluded in their hopes from both sides, as we were beaten before Tayowan and they before Siccam. They were all caught and killed one after the other.

So far the thoroughfare to our ships had been unimpeded, allowing us to take everything we needed, but now the enemy endeavoured to take the passage away from us. To that end they sailed some of their war junks into the mouth or inlet of the harbour. We from our side constructed at the far corner of the beach a wooden breastwork with two mounts upon which we placed heavy guns which we could use to shoot over water. Furthermore our pilot boat was loaded with special fireworks and gun powder, covered by a second floor for sailors who were well able to swim. These men put the boat under sail as if they wanted to make their way violently amidst the war junks of the enemy. They were attacked on both sides and all Chinese who were able to reach them jumped into the ship. The sailors lit the fire unseen, jumped overboard and swam out of the way. And a good number of the enemies who had jumped aboard were blown into the air. They refused however to leave the place with their junks until, finally, from our new stronghold we shot some of their ships to the bottom and caused great havoc among them. Now the passage was reopened for us.

At this time one of our sergeants and three soldiers defected to the enemy and explained to them how to first hit the redoubt.

In the end of September three ships were prepared with crew and provisions to sail to the Pescadores to fetch more cattle for the sick and the wounded. As our ships sailed in that direction, the enemies had reinforced there (on the Pescadores) and hid. Our men didn't suspect anything and as a result stepped carelessly from the ships ashore, some here, others there, without staying together. But unexpectedly the enemy with all its troops raided our people, caused them great harm, clubbed many of them to death and wounded some others. Ten of them they caught in the water and sent in fetters to their king (the one from China) at Tayowan. As soon as they had arrived, their noses, ears and right hands were cut off by order of the king and with the severed hand fastened on their necks they were one after the other sent to us in the fort. Among these ten was a Frenchman. He was recognized by a compatriot who had recently defected to the enemy and implored them that he would be permitted to keep his hand, which was allowed.

Around this time Captain Outshoorn arrived from the island Lambay, to which he had departed some weeks before. He had also visited the area on Formosa in front of the island of Lambay to investigate whether the inhabitants would turn out to be hostile against us. He sent a longboat with some soldiers, one of them with a letter for the natives who stood in a large crowd at a gunshot's distance from the shore. He did not come back and so there was no answer on the question. Then someone else offered his services. He was able to speak with the natives in their language (as he had been for several years a school teacher there). He hoped that he would be welcomed by them, even hoisted into the air. When he came among them, they paid him great homage, but when he had finished his speech they chopped his head off. And all cut a piece of flesh from him. This was the way they hoisted him into the air after his death.

Having found out clear enough that the inhabitants were hostile against us, they sailed away from them, to Tayowan, to the fort. On his course he met a raft with three Dutchmen, who told Captain Outshoorn that they had come with eighty persons from Pinaba, where they had stayed for a long time. They had already sent a raft with three men to ships before, but they had not come back. They explained their situation. As they had often been pursued by the natives and had been forced to fight their way through, they had a dire shortage of gun powder and lead. These goods were procured to them and a day was fixed a few weeks ahead for them to assemble in order to be picked up by a ship. Thereupon they went on sailing.

On 18 October this Captain Outshoorn was ordered to sail with a well-manned galiot and a pilot ship to Baxamboy to destroy the batteries there. The enemies however received intelligence about this and our men were received with gunfire and forced to retire with great losses.

As we realised that we were altogether too weak to repel the enemy, we knew we had to look for help elsewhere. To this end five ships were directed to the Chinese mainland to send from there an envoy to the emperor in Peking. Admiral Cau, who had come to our assistance from Batavia, joined them. He brought a precious present with him to honour the emperor of the Tatars, the great Cham, hoping that it would facilitate fulfilment of his wish: that he would support us with his armies against these Chinese who were also his enemies. Their plans were however marred by a fierce tempest on their outward journey. They were scattered and the admiral and two other ships that had remained together, but had already been strayed far from their course, sailed to Siam where they provided their ships with the first necessities and sailed on to Batavia.

The other two ships reappeared after a long time at Tayowan, as they had not found the other three on the Chinese shore, where they had waited for several days. So we lost all hope for assistance again and the enemy, who heard it from defectors, triumphed. This way the defectors procured them new motivation and encouragement to continue and intensify their attacks.

Early December, Captain Aeldorp was sent with two ships carrying fifty healthy and hundred sick and wounded persons to the island of Lambay to refresh themselves with coconuts and other fresh fruits and vegetables. When we had arrived on the shore all longing for fresh vegetables and fruits, one went here, the other there and so we scattered over the place. Some accidentally ran into Chinese and were pursued. So they went back to the gathering place to inform the Captain, who swiftly sent a longboat with men and a helmsman to row around the island looking out for Chinese junks. When they had made their round and no junk was seen, they reported this and made another trip to a sandy place where they could land and which they had noticed before. There were many coconut trees some of which they cut down to gather their fruits. In the meantime a big company of fully armed Chinese seized the longboat and set it on fire. They clubbed the helmsman and two sailors; the others jumped into the water. Several found their way through the jungle to our gathering place. As soon as we heard this, a sergeant with twenty men was sent out. We found four Chinese that had stayed behind to strip the longboat of its ironwork. Two of them were shot and the other two fled to the rocks, to their caves, to which they had to climb ladders that were withdrawn when they had reached them, so we could not catch them. So we had to return to our army camp.

And after we had loaded our ship with wood and coconuts we went to the other side, to Formosa, where we picked up the eighty above-mentioned persons. From there back to Tayowan, as at that moment the fort was surrendered to the Chinese.

During our absence the enemy had as a first measure installed some batteries behind the redoubt and shot a breach, a storm gap, in it and then at clear daylight placed the ladders for the assault. Our men were well provided with hand grenades, stink bombs and all kinds of explosives to defend themselves, causing the enemy with great loss of men to retreat once again. They resumed their intensive shooting to widen the breach. The governor ordered our men, who were not able to resist any longer, to leave the redoubt, lighting a fuse in the ammunition cellar that still contained several crates with gun powder. Then they went to fort Zeelandia. As soon as the Chinese noticed that the fire was not returned, many of them went up to the redoubt thinking there was some looting to be done. When the fuse had burned down and lit the powder, the redoubt exploded with a loud blast with all the men in it. They shouted to us that we had not acted according to the war customs but as murderers. So they resolved to storm the stronghold with all their might and not even to spare a baby in its mother's body. They built another battery on the place where the redoubt had been, to which they carried various guns that shot 36 pound of iron. Soon they had shot breaches between Bastion Amsterdam and Bastion Gellerland where the walls were weakest. We were not able to remedy as no wood or other material was available. So our men decided to fight till the last man, which was approved by the officers as well, as there was no other hope of salvation than an assault, preferring to die cavalierly defending ourselves on the battle field against the enemy.

But our Governor was not willing to allow this and decided to come to an agreement with the enemy if possible. He sent an ambassador who was promptly interrogated and sent back with the promise that an accord would be reached. Quickly two members of the council, N. von Iperen and Harthauer were sent, to whom they sent three of their commanders.

So the treaty of 10 February 1662 was concluded: that our men, altogether about 900 healthy and sick, were to retreat fully armed and with flying banners. They were however to leave all goods in the fort and to fire all guns in their presence to take away any suspicion on their side that some trap was hidden in them. This treaty was held and our men subsequently led to the ships, where we stayed a few other days until everything had been transferred to us according to the agreement. One of our ships was sent to the Chinese shore, to Guangdong, to take along the imprisoned commander of Siccam. Our ships however set course for Batavia.

The whole island, especially where flat, is very fertile for various crops, like corn—just like that of Europe—a good rice and various tubers. Batata-roots and yams are abundant and very healthy and good to eat. The same with white sugar and all kinds of tree fruits, such as lime and sour and sweet lemons &c. There are not many harmful wild animals here, as on the other Indian islands, very few snakes and no crocodiles at all. However such an incredible mass of deer that one wonders where they all find their food. The deer are peaceful, fat and fully fleshed. Throughout the year the Chinese and Formosans shoot and catch an infinite number of them. They salt the meat, dry it in the sun and sail the whole ship full to China's shore. What remains is sent to Japan to be marketed there. Furthermore there are many wild horses, buffaloes and boars. There are also many domestic animals, cows, sheep, pigs and all kinds of birds. There is good fishing from the shore around the island and additionally with a northern wind whole schools drift around and jump on the shore. They are caught in ship load quantities and salted.

The Chinese, even if blind heathens, believe in a God who created the heaven and the earth, rules Sun and Moon and also bestows growth to the trees and the plants. This God they call Ziqua in their language. In their temples (with preciously incised woodwork, usually built with four pillars at the edges and lacquered externally as well as internally, that is, covered with so-called Spanish sealing wax that is applied upon it) one finds, next to many other admirable images, sculptures with five, often seven heads, of usually three gods, artistically cut from sandalwood, painted and gilded.

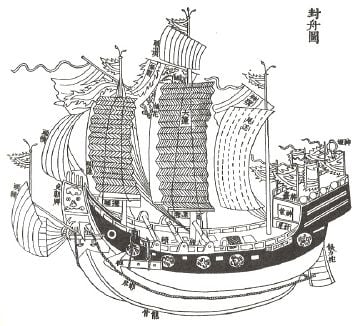

One of them is an image of the devil with a big lion head, but for the rest like a human, except it has big, curved nails on its hands and feet. It sits in all its splendor on a throne and is called Joossi by them. The second who sits on a throne at its right side, is styled like an old man of their nation, with regard to posture as well as to clothing. So they think that their lineage stems from this one. The third who sits at Joossi's left side, is a statuette of a woman, whom they believe to be an inventress of boats and rudders, explaining that she invented them after studying a fish which steered itself to and fro with its tail. They offer their sacrifices to this statue after acts of navigations, or planning them.

They keep these three deities not only in their temples, but in all their homes, on a kind of altars that are draped all around with all sorts of painted and gilded paper. They offer their deities each day fresh food that they subsequently give to their slaves. In front of them three wax candles burn day and night and often three for each of them, coloured with red paint and inscribed with gilded characters. Each day they also burn precious incense for them, gilded paper and sandalwood.

The Chinese marry only one wife, but they are allowed to have as many concubines as they want. However, the only heirs to the father are those children that are born from the only wife he was married to. During the youth of the girls born to their lawful wives, small wooden shoes, about the size of a fist, are fixed over their feet. These they must wear all their life to forestall their feet growing bigger than that shoe. The purpose is to inhibit them from wandering outside the home and being seen. Children that are born from other women don't inherit anything from their fathers, but are held as slaves, as far as it regards sons. The two first girls however are drowned as soon as they are born, or the mother may raise them outside the home. The third daughter is raised at home and used to serve the children born in wedlock.

The graves are covered by a vault, three steps high, looking like a furnace. When someone is buried, all the friends of the dead person come, bringing all kinds of food which they have bought. They place it at the grave and let it stand till the following day, next to lit candles. Many friends bring paper with them on which gilded characters are written, which they burn next to other incense of sandalwood above the grave.

The Chinese are assiduous workers, they spare no efforts, are very creative in silk and velvet weaving, they have bright minds, are well versed in commerce, astronomy and navigation. Even if using the compass and the magnet, they are not able to distinguish more than the four head winds. They know how to make highly artistic fireworks that hardly finds equals. Furthermore, once they have seen something, they want to make it themselves. They are remarkably given to games, partly with cards, partly, and mostly, for money, in a way that many have gambled away all their possessions and belongings, wife and child, up to their hair which in the end they cut off to stake it for a certain amount. And when they finally have gambled their hair away, they are done for and are no longer respected and when they still want to live on, they are enslaved.

They wear a long garment down to the knees over long wide trousers of white cotton or Plangi. Around their waist they wear a red satchel of cloth. They don't use headgear, except for some, mostly rich men, who wear a black embroidered silk cap that covers half of their forehead. They pull all long hair, of men as well as of women, backwards and tie it together behind the head. They shave their beards but for a few hairs that can be counted. They let their finger nails grow long, usually half a finger long.

The Chinese eat much fat fish and bacon, all kinds of garden crops. In stead of bread they eat rice and all kinds of fish. At dinner each person has his food separately before him, in small porcelain cups, in which one often finds a good dozen of different foodstuffs. They don't use a spoon, but have two round sticks between their fingers, about one span (23 cm) long, with which they know how to take hold of bigger pieces of food, such as meat that has already been cut into pieces. Finally they bring the cup to their mouth and shovel the remaining sauce and rice rest in with the sticks. The beverage they drink at dinner is strong and is drunk very hot. It is called Gucij. Furthermore during the day they drink tea-water. This they boil with the herb Tea, which grows in China, and drink it very hot, eating candied fruit and all kinds of sweets with it. This tea-water is not only drunk by Chinese but by all Indians and even by the Dutch. It is considered a good medicine.

After we had surrendered the beautiful Fort Zeelandia on Taiwan to the Chinese and had sailed off from the island we arrived on the same day at the Pangsoia river, where we anchored with the intention to fill the barrels with water. When however the boat had crossed to the shore and back three or four times, it started to become dark and a south wind rose so suddenly that we had to cut all our anchors to get away from the shore and had our flute, the Lunen, almost stranded. We were already in the surf, being driven to the shore, and soon would have been at a cable-throw distance from land. Our Lord has assisted us in turning the ship with a miraculous swiftness and saved us.